The Marquis’ Greek vasesThe Galerie Campana

This long row of rooms houses thousands of vases, cups and containers of all shape and sizes. The gallery offers a comprehensive overview of ancient Greek pottery. It is named after the collector who is responsible for bringing most of these objects together, the very colourful Marquis Giampietro Campana.

A costly collection

The Marquis Giampietro Campana (1807–1880) had one of the most extensive private collections of art that Europe had ever known. It consisted of thousands of ancient objects, as well as many Italian works from different periods. Indeed, the Marquis Campana wanted to build a collection that represented the breadth of artistic production in all of Italy. From the start, he bought many works of art, and even took it upon himself to organise archaeological digs.

But his passion came at a price that neither his personal fortune nor his salary as director of the Monte di Pietà – a charitable institutional pawnbroker in Rome – could afford. In 1857, the Marquis Campana was arrested for financial foul play. His collection was confiscated and put up for sale. Many art lovers looking for a deal came from all of Europe, including the Tsar Alexander II and Emperor Napoleon III. The latter bought the bulk of Campana’s collection with his personal funds: thousands of ancient works and hundreds of Italian paintings. The emperor had them displayed in French museums, notably the Louvre and the Petit Palais in Avignon.

A 19th century re-shuffle

Prior to the arrival of the Campana collection, these rooms had already been used to display art since 1819. In the early 19th century, the Louvre’s collections were expanding thanks to archaeological finds and acquisitions, and new sections were opened up all around the former palace, like the Galerie d’Angoulême and the Musée Charles X. This was the golden age of the architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, who were busy working on all the projects, including this one.

When Napoleon III bought a large part of the Campana collection in 1861, he decided to showcase it here, asking his architect Hector Lefuel to think up a new décor.

A costly collection

The Marquis Giampietro Campana (1807–1880) had one of the most extensive private collections of art that Europe had ever known. It consisted of thousands of ancient objects, as well as many Italian works from different periods. Indeed, the Marquis Campana wanted to build a collection that represented the breadth of artistic production in all of Italy. From the start, he bought many works of art, and even took it upon himself to organise archaeological digs.

But his passion came at a price that neither his personal fortune nor his salary as director of the Monte di Pietà – a charitable institutional pawnbroker in Rome – could afford. In 1857, the Marquis Campana was arrested for financial foul play. His collection was confiscated and put up for sale. Many art lovers looking for a deal came from all of Europe, including the Tsar Alexander II and Emperor Napoleon III. The latter bought the bulk of Campana’s collection with his personal funds: thousands of ancient works and hundreds of Italian paintings. The emperor had them displayed in French museums, notably the Louvre and the Petit Palais in Avignon.

A 19th century re-shuffle

Prior to the arrival of the Campana collection, these rooms had already been used to display art since 1819. In the early 19th century, the Louvre’s collections were expanding thanks to archaeological finds and acquisitions, and new sections were opened up all around the former palace, like the Galerie d’Angoulême and the Musée Charles X. This was the golden age of the architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine, who were busy working on all the projects, including this one.

When Napoleon III bought a large part of the Campana collection in 1861, he decided to showcase it here, asking his architect Hector Lefuel to think up a new décor.

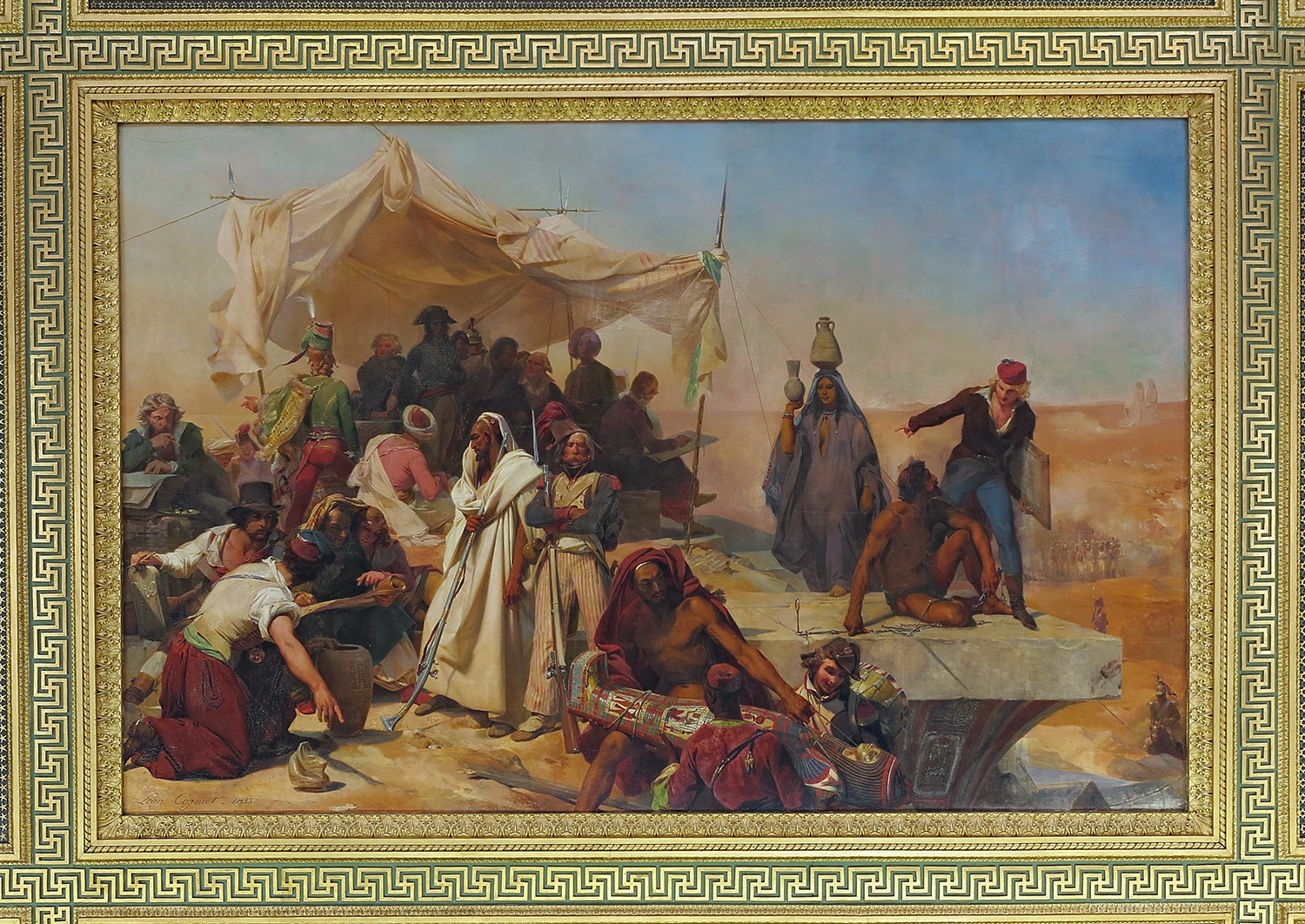

Ceilings steeped in history

Lefuel decided to keep the ceilings that were painted between 1828 and 1833. The themes they feature were appropriate for the new function of the gallery: the patronage of the kings of France. The most famous French sovereigns are portrayed as protectors of the arts: Charlemagne, Louis XII, François I, Henri IV, Louis XIII, Louis XIV, etc. Even General Bonaparte is up there, in L’Expédition d’Égypte, which evokes his military campaigns in Egypt but also the scientific and artistic research he sponsored.

Cette salle d’introduction à la galerie Campana présente le vase grec sous trois aspects : les formes (le vase est un objet manipulé au quotidien), les techniques (comment fait-on et comment peint-on un vase grec ?) et enfin les images, d’une richesse sans équivalent et qui nous introduisent notamment au cœur de la mythologie grecque. Servie par un accrochage spectaculaire, cette salle pédagogique, assortie d’un dispositif tactile sur les formes et d’un multimédia sur les mythes, donne des clés pour comprendre et aimer la céramique grecque en invitant à poursuivre l’exploration sur l’ensemble du parcours.

La galerie Campana

An encyclopaedia of Greek pottery

Since the purchase of the Marquis’ collection, the Galerie Campana, enriched with new acquisitions, has remained exactly what the original collector would have wanted it to be: a comprehensive overview of Greek pottery. It is made up of a room to introduce Greek vases, followed by rooms for studying pottery and a chronological display spanning the 9th to the 1st centuries BC. It includes examples of all styles, all time periods and all centres of production. It’s like a giant walk-in encyclopaedia!

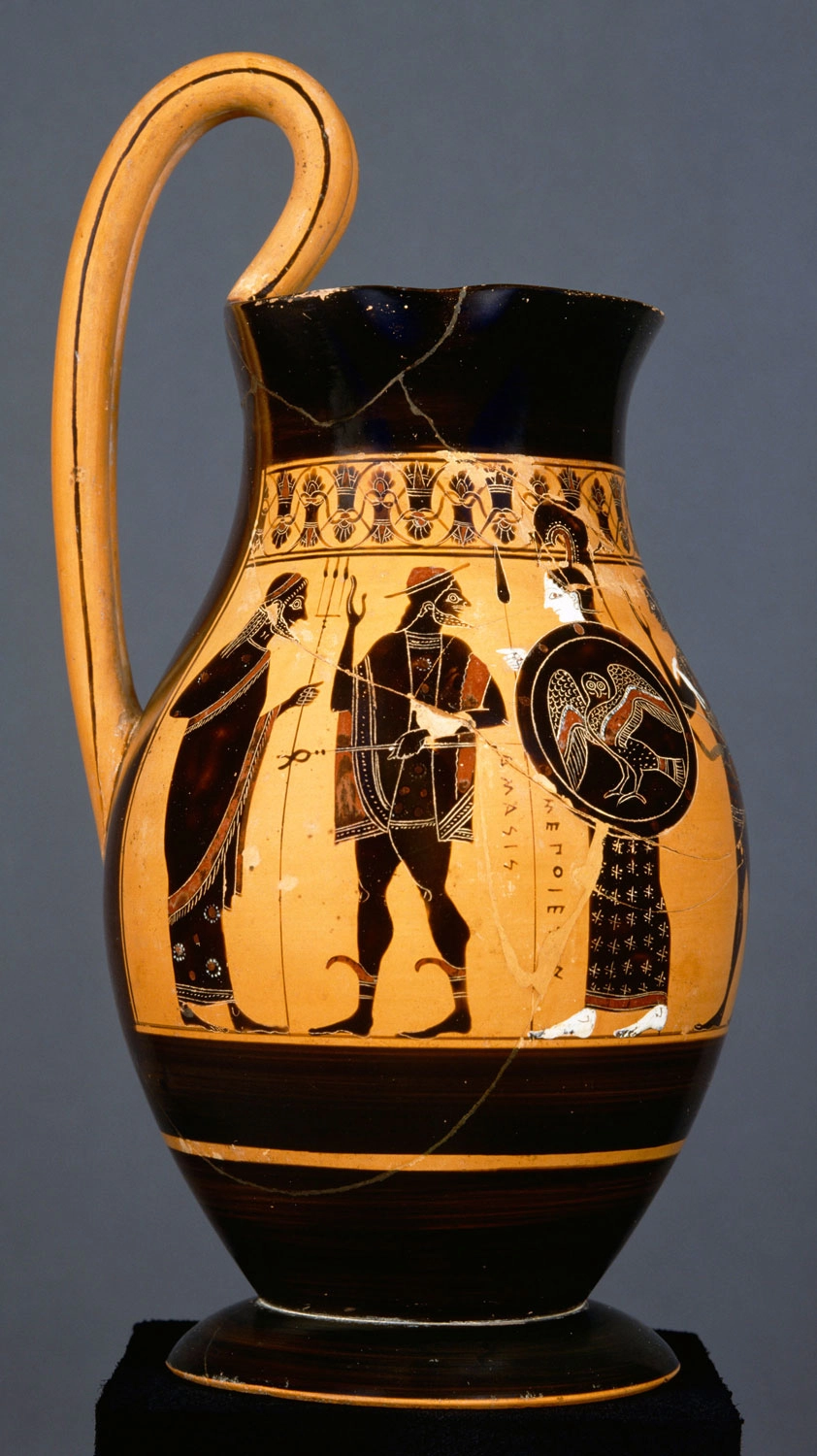

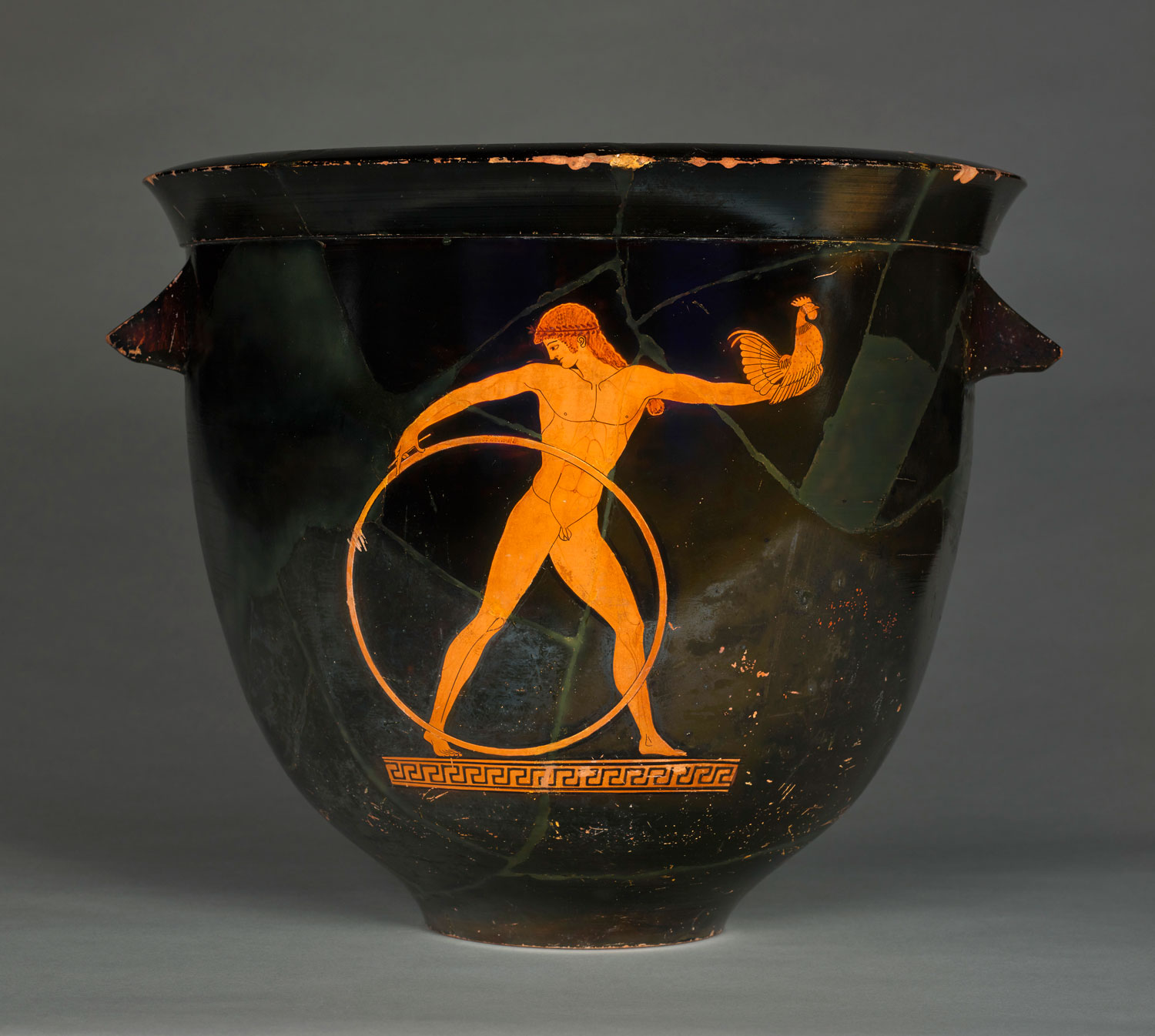

The vases on display bear witness to technical progress: the use of the potter’s wheel, and notably fast turning which lends well to more regular forms. Thanks to improved kilns, the firing process was perfected. Potters managed to achieve an intense black sheen that is the hallmark of Greek pottery. Vase decoration also evolved dramatically: geometric at first, they gradually featured animal and then human figures, until finally depicting whole scenes, recounting myths and battles or offering a glimpse of everyday life.

Refermées en 2003 pour servir de réserve transitoire, dans le cadre du plan de prévention contre la crue de la Seine, les salles d’étude offrent une présentation densifiée des collections, classées selon un principe chronologique et typologique (par formes). Dotées de tables de consultation, ces salles accessibles à tous sont destinées le mardi à l’accueil des chercheurs.

Les salles chronologiques

Ces salles (655-651) - à visiter dans ce sens pour respecter l’ordre chronologique, proposent un parcours à travers un millénaire d’histoire (du 10e au 1er siècle avant J.-C.) comprenant des chefs-d’œuvre et des objets de série, classés par époque et centres de production. Une véritable encyclopédie !

Les vases exposés témoignent de progrès techniques : l’utilisation du tour de potier, notamment du tour rapide, permet de créer des formes régulières. Grâce au perfectionnement des fours, la cuisson est mieux maîtrisée. Les potiers parviennent ainsi à obtenir ces noirs intenses qui ont fait la gloire de la céramique grecque. Les décors connaissent eux aussi d’importantes évolutions : d’abord géométriques, ils se peuplent peu à peu de figures animales puis humaines, jusqu’à devenir de véritables scènes, racontant des mythes, des scènes de combats ou de la vie quotidienne.

Outre la révision de l’éclairage qui transforme radicalement l’expérience de la visite, l’introduction d’une carte disposée dans l’alcôve située entre les salles 655 et 654 permet de visualiser la dynamique des échanges et de localiser les lieux de production et de découverte, deux éléments essentiels des cartels.

Masterpieces of Greek pottery

Attic geometric krater

1 sur 12

Did you know?

Hidden clues…

When a décor was created for the Galerie Campana, the choice was made to keep the painted ceilings. Indeed, the scenes they feature fit well with the collection below. But if you look carefully, you will notice small clues as to what these rooms were formerly used for. It was here that a collection of decorative artworks from the Renaissance was housed, and some are peeping down on us from these ceilings…

Le saviez-vous ?

Le « miracle » de la cuisson

Bien que la gamme des couleurs soit, à quelques exceptions près, assez réduite, les vases grecs offrent un aspect très chatoyant, qui est dû à la cuisson. La cuisson est une étape essentielle dans la fabrication du vase : elle donne au vase ses qualités de résistance et d’imperméabilité. La cuisson en 3 phases, parfaitement maîtrisée par les potiers grecs, révèle aussi les décors grâce au contraste créé entre la peinture noire (une argile utilisée pour les décors) et la couleur claire et naturelle de l’argile. Le contraste est particulièrement fort sur les productions d’Athènes : sur les vases à figures noires, les figures sont dessinées en noir sur le fond clair du vase ; sur les vases à figures rouges, les figures se détachent en rouge sur le fond noir du vase.

Did you know?

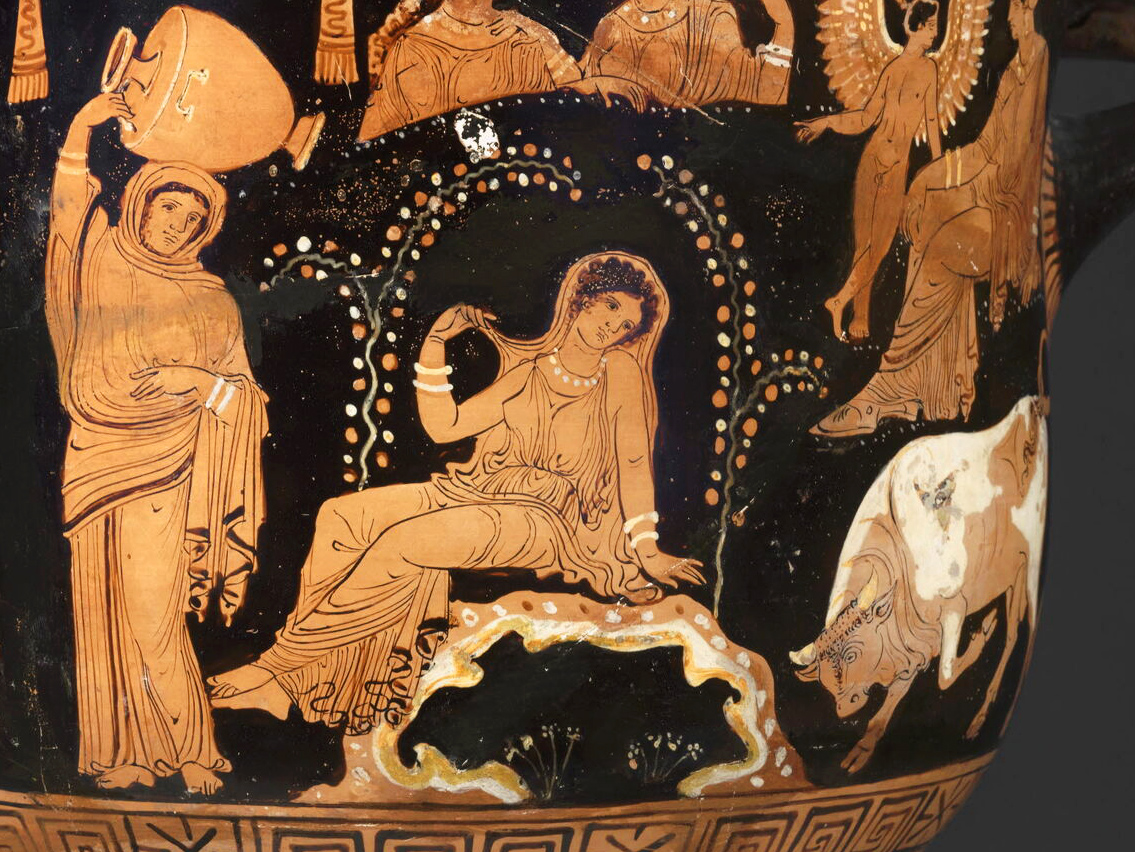

The face of Europe

The European Central Bank was in the market for a face of Europe for its bank notes, and the Louvre had just the thing. The figure of Europa (a young woman loved by Zeus who changed himself into a white bull and carried her off to the continent that would later bear her name) on a crater vase made about 360 BC now features as a watermark on Euro notes.

More to explore

A Royal Setting for Egyptian Antiquities

The Musée Charles X

Ideal Greek Beauty

Venus de Milo and the Galerie des Antiques